The Red Coronation

“I’m On A Boat” / “The Red Coronation” / “The Bishop In Black” /

“The Red Bishop” / “A Time to Sow” / “A Time to Reap” / “From Emma, With Love”

Marauders #1-7

Written by Gerry Duggan

Art by Matteo Lolli, Lucas Wernick, Michele Bandini, and Stefano Caselli

Color art by Federico Blee with Erick Arciniega and Edgar Delgado

Marauders is a peculiar series, both the most radical of the new Dawn of X series in concept and the most traditional in its storytelling. Gerry Duggan is enthusiastically exploring the possibilities of the new ideas Jonathan Hickman introduced in House of X/Powers of X – the issues of trade and diplomacy that come from both Krakoan sovereignty and the miracle drugs that drive its economy, the rebranding of the Hellfire Club as the Hellfire Trading Company, the quirks of Krakoan gates, the utility of the resurrection protocols – and is doing it, in of all things, a pirate comic. I was initially wary of the clean, direct “house style” art and emphasis on humor and action/adventure, but seven issues into the series it’s clear to me that Duggan is playing to his strengths as a writer while taking Hickman’s concepts very seriously.

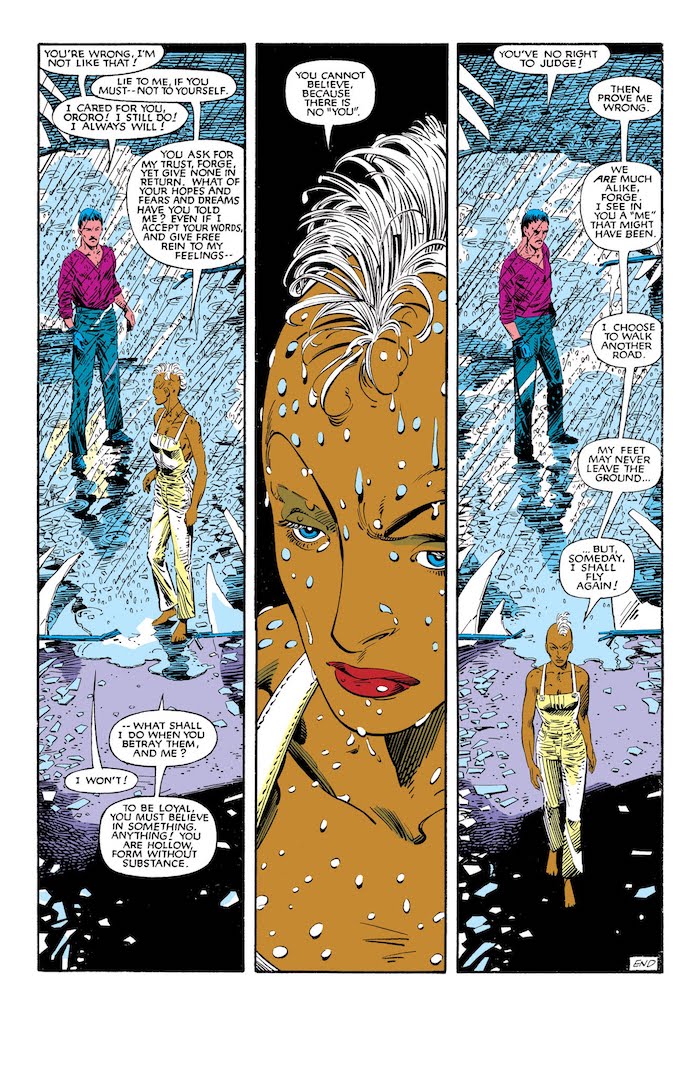

This is an ensemble series, but the star is clearly Kitty Pryde. Pryde, who now wishes to be called Kate rather than Kitty, is mysteriously unable to pass through the Krakoan gates and can only get to the living island by boat. In the first issue Emma Frost, the White Queen of the Hellfire Club, offers Pryde a seat on the Quiet Council of Krakoa in exchange for becoming the Red Queen of the Hellfire Club and heading up both the distribution of Krakoan drugs and missions to rescue mutants around the world who cannot find a way to Krakoa. Pryde is accompanied by her close friends Iceman and Storm, the mutant cop Bishop, and the newly resurrected and reformed villain Pyro. Sebastian Shaw, the Black King of the Hellfire Club, is the book’s primary antagonist and is actively scheming against Frost and Pryde.

Each lead character in Marauders gets some fun moments, but it’s pretty obvious that Duggan is invested in Pryde above all else, and is doing what he can to push the character forward after a few decades of stagnation. The usual problem with the depiction of Pryde is that she’s often written in an overtly nostalgic way by authors who grew up in the early 80s, and that she’s frequently presented as a moralist scold. The latter bit doesn’t have to be a bad thing – it is a legitimate personality flaw that’s been with her since the beginning and it can be genuinely interesting – but Duggan seems rather pointed in steering clear of all that and emphasizing the ways she’s become willing to make ethical compromises. Duggan’s Kate Pryde comes across as a young woman who is so sick of her usual goody-goody patterns that she’s becoming reckless in search of a new identity – she’s more ruthlessly violent, drinking heavily, getting tattoos, and leaning hard into the whole pirate aesthetic. She also seems very depressed and lonely, and I trust Duggan to dig deeper into that as he goes along.

It doesn’t always work, particularly in the first few issues. There’s a text page in the debut issue in which Wolverine sends a message to Kate asking for a list of goods, foods, and beverages to bring to Krakoa that is both wildly unfunny and nonsensical given that he’s a person who can freely teleport anywhere he wants, and she’s a person who is stuck taking long boat rides everywhere. Duggan fumbles some early story beats by delivering things we’ve already accepted as the high concept of the series, such as Pryde becoming the Red Queen, as big issue-ending reveals. Storm, a Quiet Council member and second to only Cyclops in the chain of command of the X-Men, doesn’t quite make sense as a subordinate supporting character in this series despite her close relationship with Pryde and only seems to be in the book because Duggan called dibs on her very early.

Duggan’s greatest strength in writing Marauders is that while the circumstances of the story are exploring new ground, the relationships and motives of the characters are firmly rooted in continuity without getting bogged down in rehashing old stories. Frost and Pryde, introduced in the same issue back in the Claremont/Byrne era, have a long and complicated history together, and Duggan pushes them into a new phase of mutual respect and collaboration after too often being written as petty rivals who cruelly condescend to one another. Storm and Iceman are two of Pryde’s closest friends in the X-Men, but are also two people who’ve had very painful histories with Emma Frost. When Callisto is reintroduced in the seventh issue, Duggan gracefully acknowledges her contentious relationship with Storm, her past with the Morlocks, and her brief career as a model. I particularly like when Callisto shows a grudging respect for Pryde taking the name of the Marauders, the kill crew who slaughtered the Morlocks and nearly ended Pryde’s life in the “Mutant Massacre.”

Marauders has been illustrated by four different artists in the span of seven issues, and while they’ve all been somewhat bland and functional, they’ve all matched up stylistically so the series at least has a consistent visual aesthetic. It feels somewhat churlish to complain about the strong draftsmanship of Matteo Lolli, Lucas Wernick, Michele Bandini, and Stefano Caselli, but I do wish they had a bit more flair. They’re not exactly miscast for the tone or subject matter of the book, and Lolli is particularly good at drawing some of Duggan’s most imaginative action sequences, but it looks like it could be any mid-list Marvel book as opposed to what is effectively one of the flagships of the newly ascendant X-Men franchise. I just wish it looked more fresh.

All told, I’m glad I held off in writing about this series because it’s been better with each passing issue, with Duggan deepening his characterization and steadily heightening the stakes. He’s even managed to make Jason Aaron’s Hellfire Kids characters from his dreadfully goofy Wolverine and the X-Men run a worthwhile set of antagonists in this, which is borderline miraculous. (That said, why does he take these awful little kids more seriously than Donald Pierce, a character who was presented as one of the more unhinged and terrifying villains of Chris Claremont’s original run?) But despite minor quibbles, I feel like Duggan is headed in the right direction and am grateful for his efforts in evolving Kate Pryde as a character.