The Left Hand

“The Left Hand”

Immortal X-Men #1

Written by Kieron Gillen

Art by Lucas Werneck

Color art by David Curiel

Immortal X-Men #1 flows so gracefully from where Jonathan Hickman left off in Inferno while firmly introducing a new era for the franchise more generally that it’s now even more baffling that Marvel insisted on lodging X Lives/X Deaths of Wolverine between the two stories. In every way that the latter story fumbles through plot points and inadequately “yes, ands…” Hickman’s story, Immortal X-Men artfully builds on what came before while reestablishing Kieron Gillen as an X-Men writer.

But this is no surprise, as a major strength of Gillen’s work-for-hire writing is a skill for respecting what other writers have laid down while adding new ideas and value to the ongoing story. The best example of this is what Gillen did for Mister Sinister in his first X-Men run – he effectively fully reinvented the character while using what had come before, and the Sinister we’ve known through the Hickman era is very much the flamboyant Victorian eugenicist creep that Gillen gave us. Gillen picks up the Sinister baton once more, but in a totally new context provided by Hickman – he’s a major political figure in the mutant nation, he’s been instrumental in making mutants effectively immortal, and he’s cooking up ideas for chimera gene mash-ups.

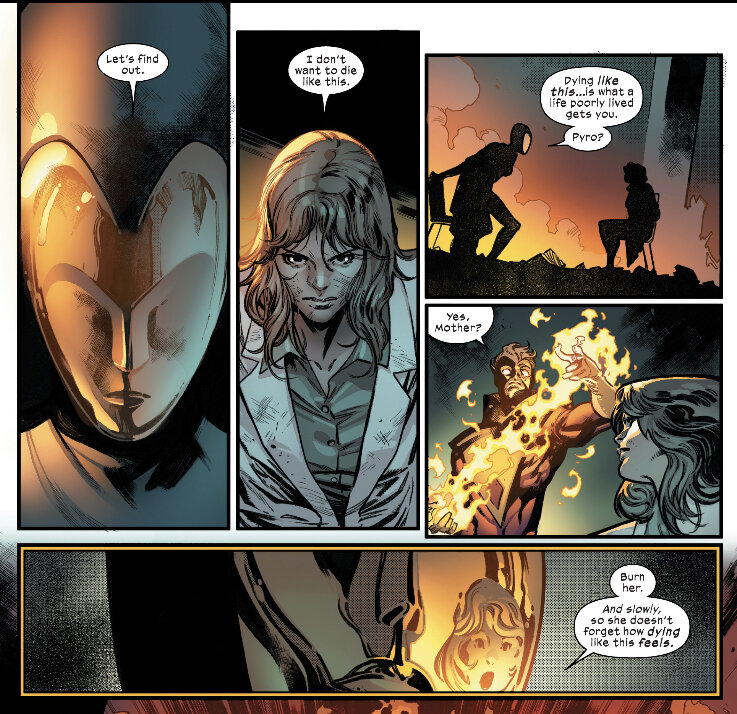

Gillen quickly reminds us of some elements of his Sinister that have been largely glossed over more recently, such as the fact that he electively became a mutant through extensive cloning of his own body and that he has no care for mutants beyond being genetic fodder for his experiments. By the end of this issue we see that Sinister has been using mindless clones of Moira McTaggert in a scheme to send information from his future selves back to the present so he can have advanced knowledge of events. He’s essentially approximating the precognitive powers of his rival Destiny, but with a difference – while she sees branching timelines ahead of her, he’s working on more empirical evidence of things that have actually happened to him, albeit in varying versions of his lived experience. It’s already shown to be a faulty system in a council vote scene, but a very intriguing development for the character and a clever spin on the utility of Moira’s powers.

But why would Sinister see Destiny as a rival? This is unclear as of yet, though the opening pages of this issue establish that the two knew one another in England in the wake of World War I, and that she told him a secret that unexpectedly killed his clone body. The scene is a deliberate echo of the Xavier/Moira park bench scene from Powers of X – the setting, the casual conversation, the woman with great knowledge passing it on the arrogant man in a way that shatters his worldview.

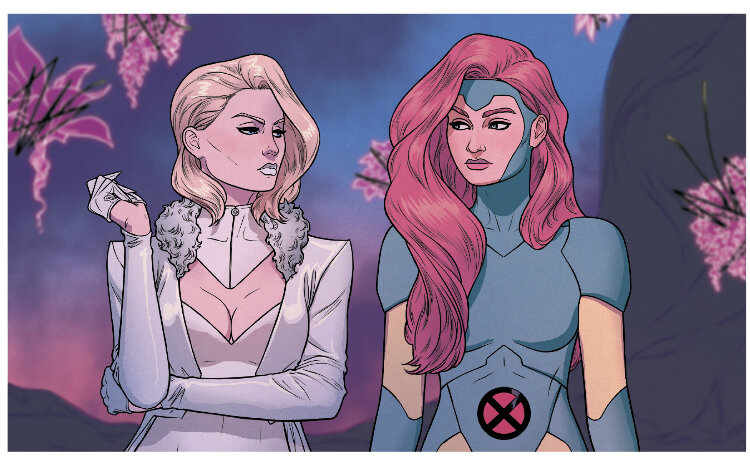

Destiny refuses to share the secret with Mystique, presumably to protect her from words so destructive they could leave Sinister dead and gasping “you’re a ghost, you’re a ghost” as he passed. But what does that mean? I don’t have a good guess at the moment, but I’m intrigued by the seemingly mystical effect of her words. The title of the issue – “The Left Hand” – would suggest that what we’re seeing with Destiny and Sinister here is a conflict between two opposing systems of magic. That, along with the sequence in which Selene reminds us of how “mutant magic” works, makes me think that “magic” could be somewhat literal here.

Destiny’s prophecies and Sinister’s messages sent back to himself through the Moira clones also make me think of the evocative recurring phrase from Grant Morrison’s New X-Men: “Are these words from the future?”

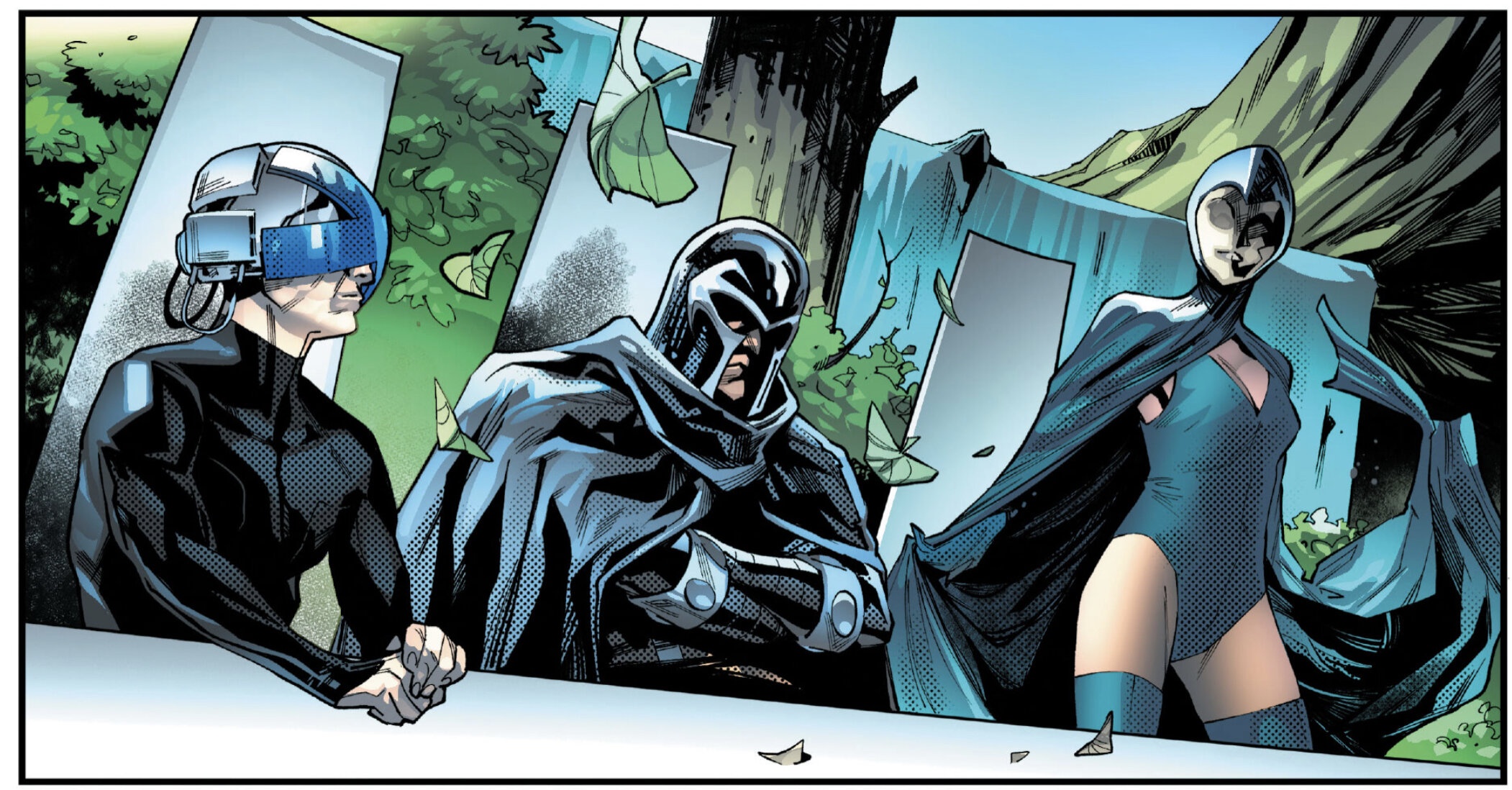

Aside from Sinister’s machinations the main plot point of this issue is Magneto stepping down from the Quiet Council in order to do whatever it is he’ll be doing on Arakko in Al Ewing’s X-Men Red, and his seat on the council being taken by Hope Summers largely due to the political maneuverings of Exodus. Hope makes sense in this book for three reasons – it makes sense for The Five to have a representative especially given their previous conflicts with the council in X-Force, Hope’s direct role in making mutants effectively immortal clicks into the title of the series, and this is a character who was central to Gillen’s previous work in this sandbox on Generation Hope and Uncanny X-Men.

As with Sinister, Hope was not created by Gillen but was largely defined by him, and so it makes sense he’d want to write her again given her “messiah” role is less a matter of narrative contrivance threading together three major X-Men crossovers and more her day-to-day job in mutant society. It should be interesting to see how she fits into this, and the suggestion that her role will directly lead to catastrophe is very intriguing. Her presence certainly does point in the direction of the Phoenix Force becoming a factor in the story, particularly as the front cover teases this with a Phoenix emblem on the empty chair at the center of Mark Brooks’ homage to The Last Supper.

One of the most promising elements of Gillen’s new run is the writer’s interest in developing Exodus, a character with a bizarre backstory dating back to the Crusades and a crucial role in the Quiet Council who often seemed like a low key insidious presence in Hickman’s X-Men. Exodus is a zealot – “a man with an unyielding code” as Xavier says in Powers of X – and a man of faith who apparently observes a sort of mutant-centric Catholicism based on his knowledge that Jesus Christ was “The Nazarene Mutant.” Exodus sees Hope as the messiah, which is at least part of why he went out of his way to bring her into the running for Magneto’s seat without consulting the rest of the council. As with most of Exodus’ actions since the beginning of the Quiet Council his behavior is noble but there’s a lingering ominousness about him. He always seems to be quietly working a long game, which makes a lot of sense for a guy who’s lived as long as he has. The scale of his life gives him a patience that the younger mutants on the council simply do not possess, and since the impact of very long lives is clearly a major topic of this run I expect that to come into greater focus in regards to him as we move along.

Miscellaneous notes:

• Lucas Werneck has stepped up his art game quite a bit for this issue, though I think the reality may be that he was simply given some time and encouragement to execute these pages on the level of the work he displays on his Instagram. Werneck’s style here strikes me as a pleasing blend of R.B. Silva and Adam Hughes, and his skill for drawing facial expressions and body language are well suited to a series in which a lot of the scenes will be people having conversations around tables. He’s also good at allowing a bit of implied space and breathing room to pages that may otherwise feel overly dense.

• Gorgon makes a brief cameo in this issue that suggests the character has settled into something more closely resembling the Gorgon we knew before his death in Otherworld, which is a major relief since the last time the character appeared he was a yelping lunatic slicing up an ice cream stand in Simon Spurrier’s abysmal Way of X.

• The one place this issue really left me wanting was Colossus basically being around to say “yes” and “no” in a few votes. It’s obvious there will be more room to explore his new role in all this in subsequent issues, but I’m just very eager to get his point of view on all this. Does he feel bewildered by this? How engaged is he? Does he actually understand that he’s a pawn for Xavier here and compromised by his brother Mikhail in X-Force? Colossus is another character Gillen has written quite a bit, so I’m curious to see his take on where he’s at today.

• The text pages in this issue really do a lot to emphasize this as a jumping-on point for new readers as well as the starting point for a new phase of the story across the line. One page early on spells out the major secrets that are moving story along – the threat of humans at large learning of mutant immortality, a recap of Inferno including the revelation that while Orchis was created by Omega Sentinel she and Nimrod do not care at all about the fate of humans, and that Abigail Brand is collaborating with Orchis. The pages at the end updating the map of Krakoa from HOX/POX is also quite helpful, as is the updated org chart for Orchis. Seriously, after the extent to which X Lives/X Deaths was hostile to new readers, this all comes as a major relief.