Un-Ring

“Alien Plants Vs. Mutant Zombies,” “Growing Strong,” “Staff Infection,” “Un-ring”

Empyre X-Men #1-4

Written by Jonathan Hickman with Tini Howard, Gerry Duggan, Benjamin Percy, Leah Williams, Ed Brisson, Vita Ayala, and Zeb Wells

Art by Matteo Buffagni, Lucas Wernick, Andrea Broccardo, and Jorge Molina

Color art by Nolan Woodard with Rachelle Rosenberg

Empyre X-Men is two things – a loose tie-in with a Fantastic Four/Avengers event and a formal experiment in publishing a mini-series as an “exquisite corpse” exercise in which each of the current X-book writers get to write a segment of the story – but is more importantly third thing, which is Jonathan Hickman setting his Scarlet Witch story in motion after teasing it in both House of X and X-Men #7. The jam elements of this miniseries are fun, especially the aspect of it that’s basically watching each writer do their best to introduce a wild plot beat before handing it off, but it’s ultimately all a bunch of enjoyable filler between the Hickman portions at the beginning and end of the series.

Since so much of what Hickman has been doing at this stage of things has been moving characters and plot points into place for bigger things later on, it’s encouraged a way of looking at the stories in terms of what’s been established or advanced. In this case, there’s some small but notable beats – we finally get to see what Angel and Monet have been up to since House of X since they don’t appear in any of the spinoff series, and we see Beast steal some science stuff from Hordeculture, the evil botanists/Golden Girls pastiche characters from X-Men #3.

Angel – who is apparently free of his menacing Archangel persona for the moment – is heading up some business operations for Xavier with the assistance of Monet, and his main plot beats amount to him being like “put me in the game, coach” to Xavier and then just bumbling around as a beautiful himbo who is objectified by most of the women in the story for the remainder of the issues. It’s all very cute and a nice change of pace from the usual angst-ridden Angel/Archangel stories, but it’s still not giving this fairly central X-Men character much to do. When notable characters aren’t in any spin-offs I assume they’re part of Hickman’s larger plan – certainly the case for Monet and Nightcrawler – but with Angel I just wonder if the writers don’t have any particular ideas of what to do with him that isn’t just going back over the Archangel/Apocalypse beats yet again.

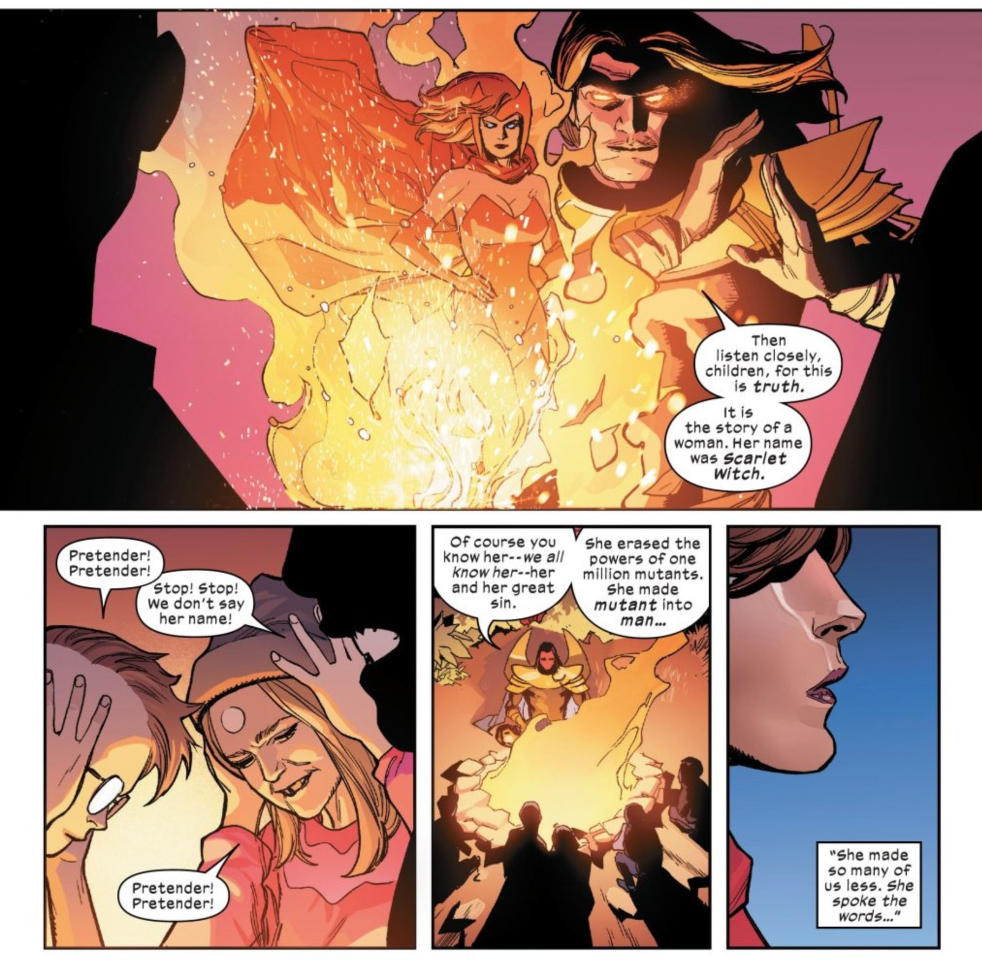

The Scarlet Witch plot goes like this: Wanda Maximoff, overcome with the guilt of stripping millions of mutants of their powers in House of M, has tried to make up for this by attempting to resurrect the 16 million mutants killed in the Genosha genocide from Grant Morrison’s New X-Men. She screws up the magic and brings them all back as zombies, and the middle section of the story is a melee with the mutant zombies, the Cotati aliens from the Empyre story, Hordeculture, and demons from Limbo. She goes to Doctor Strange to fix this and after harshly criticizing both her shoddy magic and misguided intentions, he fixes the situation on the zombie/magic end of things.

The Wanda plot is interesting to me for a lot of reasons. For one, it’s sort of amazing that in all the time since House of M was published in 2005, there’s never been a proper X-Men story that has truly engaged with her effectively destroying mutantdom for many years. This has come up in some Avengers stories, but it’s not really the same thing. Given that House of M was a thing that deliberately hobbled the X-Men as a franchise at Marvel in favor of the Avengers for many years, the anguish of mutants about “M Day” is mirrored by the people (like me!) who frustratedly read X-Men books in the aftermath of it. From an X-Men fan perspective, setting her up as “the pretender Wanda Maximoff” and having her villified by Krakoan culture feels correct both in the text and on a meta level. Wanda is a made-up character, but she represents an editorial decision a lot of readers resent.

But despite all this, Wanda Maximoff is still basically a heroic figure in Marvel lore. Even if her actions in this story create a huge mess, she’s still presented as a sympathetic figure who desperately wants to make up for what she’s done in the past. Doctor Strange’s dialogue with her in the fourth issue is blunt to the point of brutality, but he’s not wrong about her: She’s a reckless person who creates chaos and other people always have to deal with the mess she makes. She’s always trying to erase her sins rather than “eclipse them with greater deeds,” as Strange puts it. Hickman’s dynamic between these two characters is intriguing to me – he wrote Doctor Strange extensively in New Avengers and Secret Wars, but Wanda didn’t appear in any of his Avengers work. Strange is presented as very intelligent, but condescending and dismissive, particularly towards women. Wanda comes off as dim and impulsive, but very sensitive and decent at heart. Even if Strange is absolutely correct about her, Hickman pushes the reader to feel empathy for her. It’s going to be rough when she eventually has to confront who she is the mutants of Krakoa somewhere down the line.

The X-Men don’t know Wanda is responsible for the zombie mutant situation, but Wanda doesn’t know about the Krakoan resurrection rituals. This is addressed in a subplot with a mutant called Explodey Boy who first appears as a zombie and then later as his resurrected self. There’s an extended sequence in the last issue illustrated by Lucas Wernick in which the two Explodey Boys meet and talk through their odd existential situation. This very Brian Michael Bendis-y sequence is very sweet and makes good use of the possibilities of resurrection as a major feature of Krakoan life, but it grates on me that Hickman and Wernick portray Explodey Boy as a cute blonde white boy with an “aw shucks” demeanor when they had the option to make him… so many things besides a cute blonde white boy! For one thing, he looks and talks just like Cypher, so there’s a matter of redundancy. But when the entire point of Explodey Boy in the story is that he’s a wholesome normal kid, making him a blonde white boy is basically equating that with the utmost of sweet normalcy. It just seems to me that an X-Men comic in 2020 should avoid a lazy trope like that.