Fearless

“Fearless”

X-Men #1-9

Written by Gerry Duggan

Art by Pepe Larraz with Javier Pina (#4-5, 8) and C.F. Villa (#9)

Color art by Marte Gracia

X-Men is a series with a huge built-in advantage in that it’s primarily illustrated by Pepe Larraz, one of the best artists working in the medium today and one of the three people (along with Jonathan Hickman and R.B. Silva) who created and defined the Krakoa era of X-Men. Gerry Duggan is also one of the crucial foundational authors of this era as well, and it makes sense that he would be the one to be passed the baton of the main X-Men series from Hickman. Unlike Hickman’s run, which mainly served as a hub for general top level X-stories and had no particular team called the X-Men, Duggan is actually writing a clearly defined superhero team. This plays to Duggan’s strengths as established in Marauders – he’s very adept at writing old school superhero stories with an emphasis on Claremontian character development while working within Hickman’s sci-fi framework. His style is a well-balanced compromise, traditional in its structures but forward-thinking in its substance.

Duggan and Larraz, who have worked together previously on Uncanny Avengers, made their Krakoa-era debut together on Planet Size X-Men. That issue, in which the mutants terraform Mars and establish it as the planet Arakko, was very bold and easily the biggest narrative move that was not set in motion by Hickman himself. From a post-Hickman perspective it was an important move in proving the other writers had it in them to make huge, clever creative swings that were not dependent on following his plans. Particular to Duggan, it seems like the first step in asserting himself as a primary author rather than a second banana, and his X-Men run has moved along with other contributions to the macro plot that have made the series seem vital rather than a more trad continuation of Hickman’s project.

Duggan’s primary interest has been in further developing Orchis by introducing new characters and collaborators rather than focus on Hickman’s core Orchis cast of Director Devo, Doctor Gregor, Nimrod, and Omega Sentinel. The first issue introduces Feilong, the quasi-Elon Musk Chinese scientist who is embittered by the mutants usurping his plans to colonize Mars and spitefully creates an outpost for Orchis on Phobos, the moon of Mars. There’s also Doctor Stasis, a mysterious scientist with Doctor Moreau-ish tendencies and a Boba Fett-ish helmet who is intent on cracking the mysteries of mutant resurrection, and classic Marvel villain M.O.D.O.K., who is brought into the Orchis ranks on a contingent basis. The story is still in motion as of #9, but I appreciate the potential here – Feilong represents a logical response to the hubris of creating Arakko, while Doctor Stasis just… looks cool on account of Larraz’s design. As we all know, just looking really cool can take a villain very far. But it makes sense to expand the scope of Orchis’ membership, particularly as we’re meant to understand that this is a growing coalition of powers moving against the mutants. It can’t just be the same four characters working on all fronts

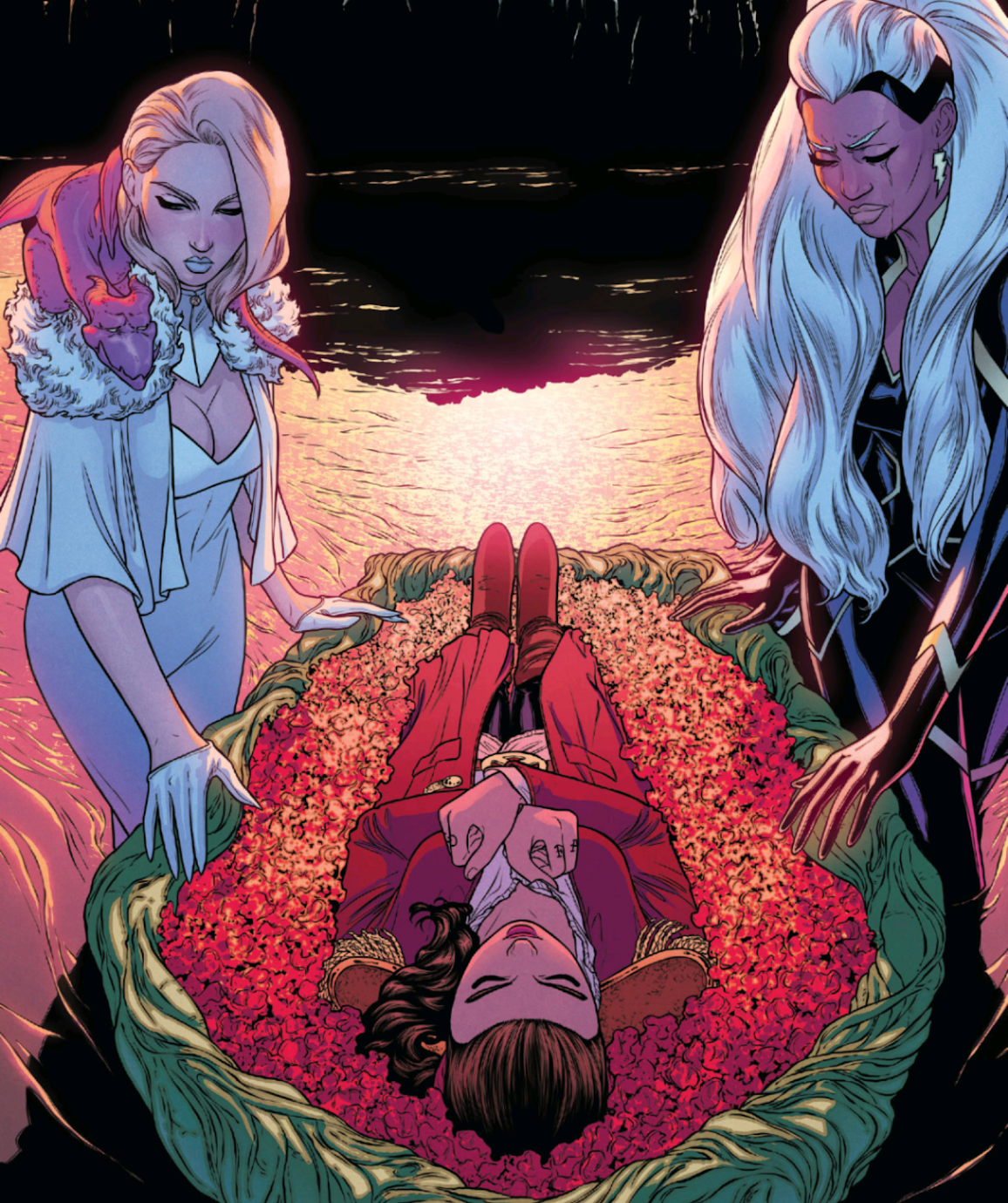

Duggan and Larraz’s X-Men is a tight team of 7 elected members – Cyclops and Jean Grey as the leaders and mainstays with Rogue, Polaris, Sunfire, Synch, and X-23 as Wolverine. (As a matter of site-wide clarity, I default to identifying that character as X-23 - no implied disrespect to her using that codename.) Duggan’s story structure is episodic with mostly done-in-one superhero plots that give space to spotlight a particular character. This has worked out pretty well, though it has been frustrating in the sense that it can give short shrift to characters who seem to linger in the wings before getting some story focus. The best example of this is Rogue, a major X-Men character who has had a fairly minor through the Krakoa era. It seemed at first that Rogue would finally get some time to shine in this series, but she’s barely around for issues on end before getting her spotlight in #9. In retrospect this was clearly a matter of scheduling – her scenes were focused on reuniting with her foster mother Destiny and that clearly had to be published on the other side of Inferno – but it nevertheless tests the patience in a monthly publication.

The two characters who’ve been best served by appearing in this series are perennial third-stringers Polaris and Sunfire. Polaris has largely suffered through the years for being written with such wildly varying characterizations that more recent writers like Leah Williams have had to settle on making this volatility a feature rather than a bug, and Sunfire has been used so sporadically that he was rather undeveloped until Rick Remender and Duggan gave him a little more interiority in Uncanny Avengers. The Polaris situation was largely resolved by Larraz, who presented her in early X-Men art as a somewhat haughty cool girl carrying a Starbucks cup into battle. This is such a clever spin on where the character is in this era – she’s the daughter of Magneto and is giving off some Big Heiress Energy while still retaining the just-barely-concealed insecurities of Williams’ characterization of her in X-Factor. Duggan has simply followed Larraz’s lead here, and presents her as someone who’s juggled a lot of potential life directions and imposter syndrome issues and is finding herself by merging all her competencies as a superhero.

As for Sunfire, it’s more a matter of this classic loner finding a sense of self-worth in service to his new nation but gradually realizing there’s other options for doing so that provide him the solitude he craves. It’s not easy to convey introversion in a superhero comic without showing an interior monologue through captions and thought balloons, but Duggan pulls this off in small gestures through the run. I can’t imagine Sunfire will be sticking around once the second team is voted in, but I do hope Duggan continues to follow the character as he gets increasingly involved in Arakko and cosmic matters, and I’m looking forward to his mission resolving a X of Swords dangling plot I’d assumed would be picked up in Tini Howard’s series.

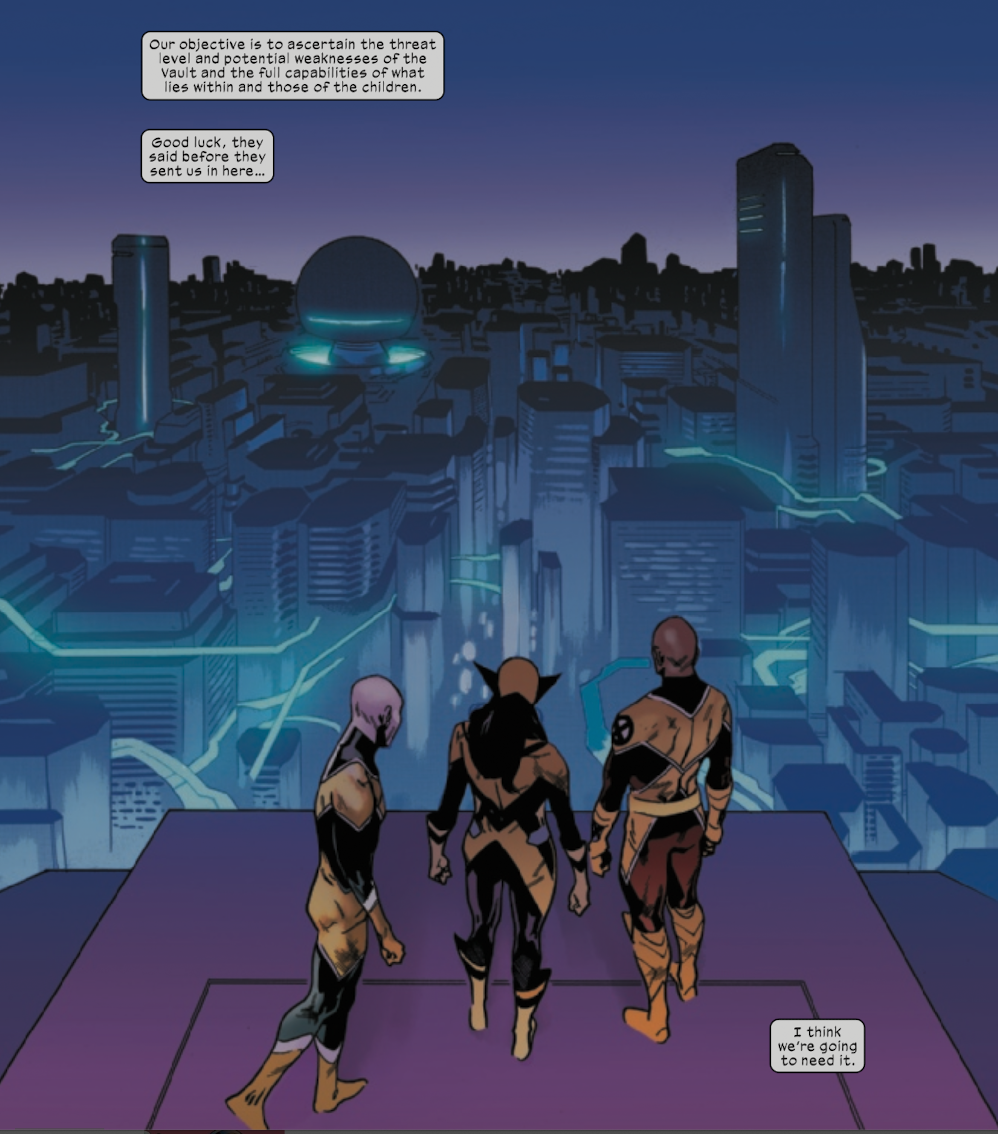

The rest of the ongoing threads range from very engaging, like Cyclops being forced to conceal his resurrection in the guise of Captain Krakoa after dying publicly at the hands of Doctor Stasis or Duggan running with the tragic romance of Synch and X-23 as established by Hickman in The Vault issues, or are in a wait-and-see limbo like the Gameworld subplot that apparently comes to a head in the next few issues. The latter is a fairly thin concept that gains a lot from Larraz’s world building and draftsmanship, which gives a somewhat mundane notion a genuinely alien appearance and some necessary razzle dazzle.

Larraz’ art is typically excellent in his issues, but thankfully he has very good understudies on this series. Javier Pina, a fellow Spaniard, has a style that merges a lot of Larraz’s aesthetics with a touch of George Perez and Phil Jiminez. It meshes well in a collection, particularly as Pina has nudged his art towards more overt Larraz mimicry in #8. C.F. Villa, who illustrated #9, also works within a similar stylistic framework, though his linework comes closer to that of Valerio Schiti. Given that some of the other X-series have suffered some lackluster fill-in artists the consistency on X-Men is to be commended, particularly as Larraz is a very difficult act to follow.